Aperture, Shutter Speed and Depth of Field

Controlling Your Camera

Shutter Speed, Aperture, Depth of Field and How it All Fits Together

Before I get into talking about how to use studio lights and how to use them to get nice photos, I want to make sure you understand a couple fundamental concepts about photography. If you don't understand these concepts, you may end up with decent shots (or you may not) but you won't control what you're doing.

Let's start this discussion with an analogy. Let's say you wanted to fill a glass of water from a faucet. You can do it one of two ways. You put the glass under the faucet and

- turn the knob very slightly to barely open the faucet, and a trickle of water comes out. You wait and wait, and finally, your glass is full. Or -

- you turn the knob all the way and the water gushes out. The glass fills up much more quickly.

Either way, you put the same amount of water into the glass, right? The difference between the two choices comes from two variables. How much you opened up the faucet and how long you let the water run. A small opening required more running time than the large opening did. Or you could turn that around and say if you wanted to let the water run a long time, you HAD to use a small opening.

Cameras work the same way, except that instead of filling a glass with water, you're "pouring" light onto the film (or the digital sensor, for digicams). Instead of filling a glass, you're allowing enough light to come into the camera to create a properly exposed image. Not too much light, not too little - just enough to give you a good shot. To do that you open your shutter (the faucet in the above analogy) and the time you let the light (the water in the analogy) come flooding in is how long you leave that shutter open.

When you take a picture, you push the shutter release. The shutter opens, allowing the light to pour into the camera. If the shutter opens very slightly, only a small amount of light is allowed in at once, and you'll have to leave that shutter open longer to allow in the proper amount of light. On the other hand, if you open the shutter wide open, much more light comes in and you don't have to leave it open nearly as long to get the proper amount of light.

This shutter opening is called the aperture. How long you leave the shutter open is called the shutter speed. With a good camera, you can control the aperture and the shutter speed. As you take photographs, you are continuously striking a balance between aperture and shutter speed to use the advantages and limitations of each while creating properly exposed images.

So why would you care if you're using a small aperture or large, or a fast shutter speed or slow?

Shutter speed

Let's start with shutter speed, because that's easier to explain.

While your camera is taking a picture, while that shutter is open, anything being photographed that moves will be blurry. Your eyes don't see it as a blur, but the camera will - like smearing paint across a canvas. You've seen pictures like that before, where someone moved while the picture was being taken and they're all blurry.

Let's say you're taking a picture of a race car going past you at 200 miles per hour. In that situation, do you want a slow shutter speed or fast? Well, that depends. You've seen pictures where everything is in focus but the car is a blur. It's a nice effect - You can just feel the motion of that car in pictures like that. In those pictures, the photographer used a slow shutter speed - for example, maybe he shot the picture at 1/60th of a second. During that 1/60th of a second, the car racing past at 200 mph actually moved about 4.9 feet, while everything else around it was sat still - so the car is a blur and everything else is very sharp.

On the other hand, if you wanted that race car to be nice and sharply focused, you'd have to shoot with as fast a shutter speed as possible to "freeze" the action and reduce blur. So if you shot the picture at 1/1000th of a second, the car doesn't have much time at all to move - it actually travels only a couple inches. It's sharp and everything else is too.

Now, looking at those two examples . . . in the first, where the photographer shot at 1/60th second so the race car would be a blur, that means the shutter was open longer - so that means he had to use a smaller aperture to ensure he didn't allow too much light in. To freeze the action he used a fast shutter speed like 1/1000th of a second. That means he'd have to open the aperture wider to allow enough light in.

In either instance, he let the same amount of light in to get a properly exposed image. It was just a question of whether he wanted to freeze the action or let the car be blurred. He controlled that decision with the shutter speed, and the shutter speed dictated what aperture he would use.

Here is a picture taken with a fast shutter speed to freeze the action:

You can tell this was taken very fast; I was able to freeze the planes in mid air so you can read the words on the wings.

Here is a photo of my nephew, Shane, taken with a slower shutter speed, to show the motion:

Shane is a good pitcher, but his fastball doesn't move as quickly as those jets in the previous picture. But notice how his arm and the ball are blurred when the jets were not blurred at all? This is because the shutter speed in the baseball picture was much slower than in the jet picture.

When you are shooting a moving subject, you will probably want to shoot in Shutter Preferred Mode rather than Programmed Mode or Fully Automatic. Shutter Preferred (it will be labeled "TV" on your camera) means that you pick the shutter speed and the camera takes your shutter speed and selects the aperture. So if you wanted to freeze that sports car you would pick a shutter speed of 1/1000th and fire away - if the camera is set on TV it will set the aperture for you. It's going to pick a large aperture to support your shutter speed. Likewise, if you want the car to be a blur you might set your shutter speed at 1/60th - again, the camera will do the work of calculating what aperture you need. This time it will choose a much smaller aperture because you're leaving the shutter open for a much longer time. Point-and-shoot cameras normally have different creative modes - if your camera doesn't allow you to control aperture or shutter speed, you would shoot in Sports mode to approximate what I'm talking about here, to force the camera to shoot with as high a shutter speed as possible to freeze the action.

That's shutter speed. It's pretty simple to understand. Now, let's turn this around to a look at aperture.

Depth of Field and Aperture

Previously we talked about managing your shutter speed to control your photos' look. Now we'll talk about situations when you would manage your aperture.

To understand this, you need to understand a term is called depth of field (DOF). DOF refers to how much or how little the area "into" your photo is in focus.

Huh?

Remember, a picture is only 2-dimensional, but you're still trying to capture 3-dimensional subjects. So even though it's hard to tell in the photo, the varying distances of the subjects to the camera influence how the picture turns out. How much of those varying distances are in focus is the depth of field.

Look at the following picture. I focused on the cat's closest eye when taking this picture. The DOF is so shallow that one eye is in focus but the other isn't. This photo has a very small DOF - anything closer than or farther than the focus point is out of focus.

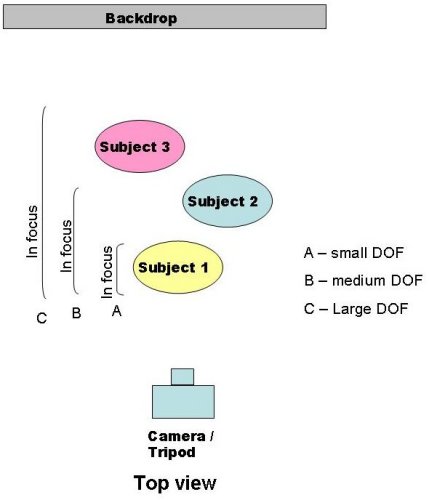

OK, let's see how this works. Let's say you had three subjects you wanted to group together in one shot. You may set them up like what you see in this graphic:

Looking at the top view (left side), you can see how they're actually set up. What you want is a really cool shot with all three of them in one shot, all close together what is shown in the camera's view on the right.

As you look at this top view, it is clear that subject 1 is actually closer to the camera than subjects 2 or 3, right? The difference might not be much (remember the picture of the cat?) but 1 is closer than 2, 2 is closer than 3, and all three subjects are closer to the camera than the backdrop. That is NOT as apparent when viewing the subjects through the camera. You can't really tell how close the subjects are from the camera's view.

DOF refers to how far into the picture is in focus. Meaning - if you use a small DOF, only a very thin slice of the image may be in focus while everything in front of and behind that slice is blurred. For example, with a small DOF, you may only see subject 1 in focus. Subjects 2 and 3 are blurry. Or maybe you focus on subject 2 and 1 and 3 are out of focus. If you increase the DOF, maybe you can get Subjects 1 and 2 in focus - even though 2 is farther away than 1 - and keep 3 blurry. As shown here:

You've got a bigger depth into the shot to work with if you increase the DOF. With a large DOF you can have all three subjects in focus and the background blurry, or you can keep going and have everything in focus.

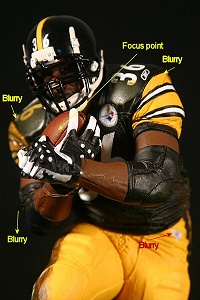

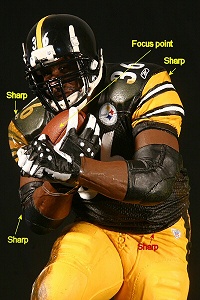

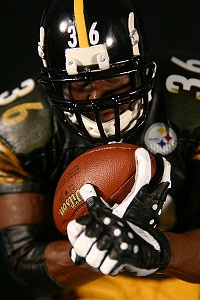

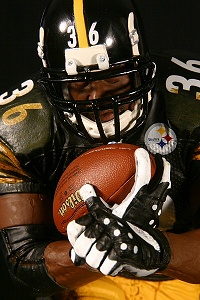

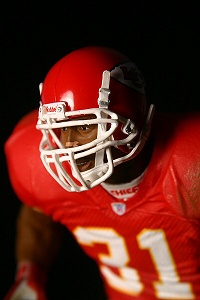

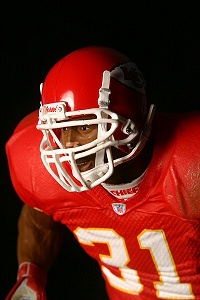

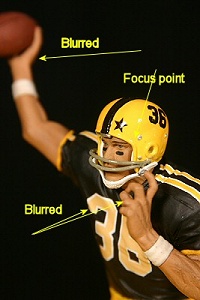

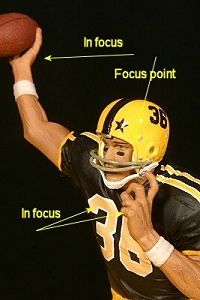

Here is an example of the same picture with a shallow and a larger DOF - click either image for a larger copy of the photo.

Shallow DOF |

Larger DOF |

|

|

Now that you understand what DOF means, you can see that the photographer can control how far into the picture one can look and see a sharp subject - whether that range of focused space is 1 inch or 10 miles deep. In a minute, I'm going to give you several more examples of DOF so you really can see the difference.

With that explanation of DOF we can go back to talking about our shutter speed and aperture.

Remember, when shooting a moving subject, shutter speed gets the priority in selecting your settings. You use shutter speed to control whether moving subjects are blurry or sharp.

You use aperture to control how large (or small) your DOF is. This is an inverse relationship. If you shoot with a large aperture - you open the faucet wide open to let lots of light come pouring through all at once - you will have a small DOF. If you use a very small aperture, a tiny opening of the shutter, your DOF will be much larger.

So for pictures like portraits or shots of specific subjects, you may want to manage your DOF and you do so by controlling your aperture. The aperture you choose will dictate what shutter speed the camera selects for the shot.

The settings for your aperture are called F-stops. You may see F-stops referenced with the letter F and a number, like f2.8 or f11. Your lens will have a lot of F-stops to choose from: f2.8, f4, f5.6, f8, f11, f16, f22, etc. and there will be intermediate F-stops between each of those. The range of F-stops you have at your disposal is driven by your lens and your camera. A low number like f4 represents a large aperture (shallow DOF). A higher number like f16 represents a smaller aperture (deeper DOF). That can really get confusing. Here are some examples.

- Aperture is 2.8 - the aperture is very large and the DOF is small.

- Aperture is 8 - the aperture is smaller and the DOF is increased.

- Aperture is 16 - now you're really getting to a small aperture and the DOF will be much, much larger.

When DOF is important you will shoot in aperture-preferred mode. (AV on your camera's dial) When you choose AV mode, you set the aperture you want and the camera will automatically calculate and set your shutter speed. Want a small DOF? Just pick f4 or whatever your lowest aperture setting you can. The camera will figure out what shutter speed you need. Want a bigger depth of field? Just run the f-stop numbers up to f8, f11, f16 . . . the higher that number, the smaller the aperture - and the larger your DOF. As you move up to f11 or f16 your shutter speed will get slower and slower, because you're using a smaller aperture so the shutter has to stay open longer. But don't worry - whatever f-stop you use, the camera will calculate what shutter speed you need and set that for you.

(Note: Another factor affects DOF - how much you're zooming in. If you shoot with a wide angle lens, like a 28mm lens, your DOF will be larger. If you put on a telephoto lens like a 200 mm lens, your DOF will be smaller. I'll show you a good example of this below.)

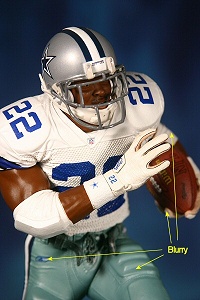

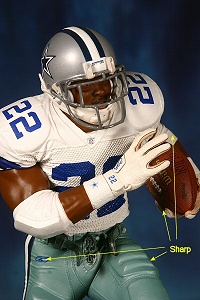

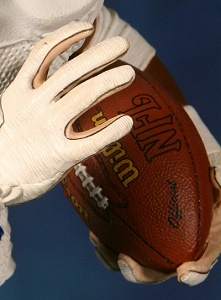

Here are some more examples to show DOF. I'm going to provide several examples because it's so important for you to understand how DOF works. Look and see what parts of the photos are in focus and what parts are blurry. Get used to paying attention to where you focus. If you have a shallow DOF, things farther away and closer than the focus point will be out of focus - it's easy to forget that. As you review these shots, you be the judge as to which works better for each shot - there isn't a correct answer. It all comes down to what you, the photographer, want to convey. The important thing to remember is, by shooting in aperture priority mode, you have the control.

Click on any picture below to view a larger version:

I used studio shots to illustrate my discussion, but here are some "real world" shots that demonstrate the lessons of this tutorial:

My brother shot this critter in his yard. Notice how shallow the DOF is - the bug's body is in focus but his leg on the opposite side of his body is out of focus and the background is a blur. And the bug is only about as big as an eraser on the end of a pencil - that DOF is SMALL. You can see how important focus is with a small DOF. The shallow DOF makes this photo much better. If the background were in focus, your eye would not be drawn to the bug nearly as much.

I shot this photo along a small canal in Venice. Notice how the building is in focus, but the birds flying through the image are a blur. A slower shutter speed made this effect possible.

Brief review:

OK, now you should understand shutter speed, aperture, depth of field and aperture. Just a brief summary to make sure you're clear:

- A properly exposed picture strikes a balance between shutter speed and aperture. Using the settings of 1/1000th of a second with an aperture of f22 will give about the same exposure as you'd get from 1/60th at f2.8, but the pictures may look very different.

- The subject matter determines which gets priority.

- If you're shooting a moving subject, shutter speed will drive your aperture. Shoot with the camera set to TV. Pick the shutter speed you want and the camera will set your aperture.

- If you want to control depth of field, aperture will drive your shutter speed. Shoot with the camera set to AV. Pick the aperture you want and the camera will set your shutter speed.

- You can further control your DOF by controlling how much (or how little) you zoom in with your lens. The more you zoom in, the smaller your DOF.

- When in doubt - Bracket!!!

What about people whose cameras don't allow them to control their aperture or shutter speed? Most digicams have a poor man's substitute for this. If you look in your manual, you'll find different shooting modes - sports, landscape, portrait, etc. When you want to have a smaller DOF, try setting the camera in portrait mode to force it to shoot with as large an aperture as possible.

Please help me get more visitors to Family Travel Photos.com!